Human capital

| Economics |

|

|

Economies by region

|

| General categories |

|---|

|

Microeconomics · Macroeconomics |

| Methods |

|

Mathematical (Game theory · Optimization) |

| Fields and subfields |

|

Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary |

| Lists |

|

Journals · Publications |

|

Economic ideologies

|

| Business and Economics Portal |

Human capital refers to the stock of competences, knowledge and personality attributes embodied in the ability to perform labor so as to produce economic value. It is the attributes gained by a worker through education and experience.[1] Many early economic theories refer to it simply as workforce, one of three factors of production, and consider it to be a fungible resource -- homogeneous and easily interchangeable. Other conceptions of labor dispense with these assumptions.

Contents |

Background

Adam Smith defined four types of fixed capital (which is characterized as that which affords a revenue or profit without circulating or changing masters). The four types were: 1) useful machines, instruments of the trade; 2) buildings as the means of procuring revenue; 3) improvements of land; and then he said,

In relation to human capital he defined it as follows:

“Fourthly, of the acquired and useful abilities of all the inhabitants or members of the society. The acquisition of such talents, by the maintenance of the acquirer during his education, study, or apprenticeship, always costs a real expense, which is a capital fixed and realized, as it were, in his person. Those talents, as they make a part of his fortune, so do they likewise that of the society to which he belongs. The improved dexterity of a workman may be considered in the same light as a machine or instrument of trade which facilitates and abridges labor, and which, though it costs a certain expense, repays that expense with a profit.”.[2]

Therefore, Smith argued that the productive power of labor are both dependent on the division of labor: "The greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgement with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour". There is a complex relationship between the division of labor and human capital.

Origin of the term

A. W. Lewis is said to have begun the field of Economic Development and consequently the idea of human capital when he wrote in 1954 the "Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour." The term 'Human Capital' was not used due to its negative undertones until it was first discussed by Arthur Cecil Pigou: "There is such a thing as investment in human capital as well as investment in material capital. So soon as this is recognised, the distinction between economy in consumption and economy in investment becomes blurred. For, up to a point, consumption is investment in personal productive capacity. This is especially important in connection with children: to reduce unduly expenditure on their consumption may greatly lower their efficiency in after-life. Even for adults, after we have descended a certain distance along the scale of wealth, so that we are beyond the region of luxuries and "unnecessary" comforts, a check to personal consumption is also a check to investment.[3]

The use of the term in the modern neoclassical economic literature dates back to Jacob Mincer's article "Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution" in The Journal of Political Economy in 1958. The best-known application of the idea of "human capital" in economics is that of Mincer and Gary Becker of the "Chicago School" of economics. Becker's book entitled Human Capital, published in 1964, became a standard reference for many years. In this view, human capital is similar to "physical means of production", e.g., factories and machines: one can invest in human capital (via education, training, medical treatment) and one's outputs depend partly on the rate of return on the human capital one owns. Thus, human capital is a means of production, into which additional investment yields additional output. Human capital is substitutable, but not transferable like land, labor, or fixed capital.

Modern growth theory sees human capital as an important growth factor. Further research shows its relevance for democracy or AIDS.[4]

Competence and capital

The introduction of the term is explained and justified by the unique characteristics of competence (often used only knowledge). Unlike physical labor (and the other factors of production), competence is:

- Expandable and self generating with use: as doctors get more experience, their competence base will increase, as will their endowment of human capital. The economics of scarcity is replaced by the economics of self-generation.

- Transportable and shareable: competence, especially knowledge, can be moved and shared. This transfer does not prevent its use by the original holder. However, the transfer of knowledge may reduce its scarcity-value to its original possessor.

Example An athlete can gain human capital through education and training, and then gain capital through experience in an actual game. Over time, an athlete who has been playing for a long time will have gained so much experience (much like the doctor in the example above) that his human capital has increased a great deal. For example: a point guard gains human capital through training and learning the fundamentals of the game at an early age. He continues to train on the collegiate level until he is drafted. At that point, his human capital is accessed and if he has enough he will be able to play right away. Through playing he gains experience in the field and thus increases his capital. A veteran point guard may have less training than a young point guard but may have more human capital overall due to experience and shared knowledge with other players.

Competence, ability, skills or knowledge? Often the term "knowledge" is used. "Competence" is broader and includes thinking ability ("intelligence") and further abilities like motoric and artistic abilities. "Skill" stands for narrow, domain-specific ability. The broader terms "competence" and "ability" are interchangeable.

Rights of Labor and Capital

In some way, the idea of "human capital" is similar to Karl Marx's concept of labor power: he thought in capitalism workers sold their labor power in order to receive income (wages and salaries). But long before Mincer or Becker wrote, Marx pointed to "two disagreeably frustrating facts" with theories that equate wages or salaries with the interest on human capital.

- The worker must actually work, exert his or her mind and body, to earn this "interest." Marx strongly distinguished between one's capacity to work, Labor power, and the activity of working.

- A free worker cannot sell his human capital in one go; it is far from being a liquid asset, even more illiquid than shares and land. He does not sell his skills, but contracts to utilize those skills, in the same way that an industrialist sells his produce, not his machinery. The exception here are slaves, whose human capital can be sold, though the slave does not earn an income himself.

An employer must be receiving a profit from his operations, so that workers must be producing what Marx (under the labor theory of value) perceived as surplus-value, i.e., doing work beyond that necessary to maintain their labor power. [5] Though having "human capital" gives workers some benefits, they are still dependent on the owners of non-human wealth for their livelihood.

The term appears in Marx's article in the New-York Daily Tribune article "The Emancipation Question," January 17 and 22, 1859, although there the term is used to describe humans who act like a capital to the producers, rather than in the modern sense of "knowledge capital" endowed to or acquired by humans.[6]

Debates about the concept

Some labor economists have criticized the Chicago-school theory, claiming that it tries to explain all differences in wages and salaries in terms of human capital.

The concept of human capital can be infinitely elastic, including unmeasurable variables such as personal character or connections with insiders (via family or fraternity). This theory has had a significant share of study in the field proving that wages can be higher for employees on aspects other than Human Capital. Some variables that have been identified in the literature of the past few decades include, gender and nativity wage differentials, discrimination in the work place, and socioeconomic status. However, Austrian economist Walter Block theorizes that these variables are not the cause of gender wage gap. Thomas J. DiLorenzo summarizes Block' s theory well: "marriage affects men and women very differently in terms of their future earning abilities, and is therefore an important cause of the male/female wage gap"[7]. Block alleges that there is no wage gap between unmarried men and women, but married men salaries are usually more than married women. These wages, he contends, are the opportunity cost of being a mother and raising children[8].

The prestige of a credential may be as important as the knowledge gained in determining the value of an education. This points to the existence of market imperfections such as non-competing groups and labor-market segmentation. In segmented labor markets, the "return on human capital" differs between comparably skilled labor-market groups or segments. An example of this is discrimination against minority or female employees.

Following Becker, the human capital literature often distinguishes between "specific" and "general" human capital. Specific human capital refers to skills or knowledge that is useful only to a single employer or industry, whereas general human capital (such as literacy) is useful to all employers. Economists view firm specific human capital as risky, since firm closure or industry decline lead to skills that cannot be transferred (the evidence on the quantitative importance of firm specific capital is unresolved).

Human capital is central to debates about welfare, education, health care and retirement.

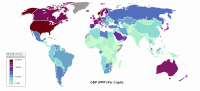

Mobility between nations

Educated individuals often migrate from poor countries to rich countries seeking opportunity. This movement has positive effects for both countries: capital-rich countries gain an influx in labor, and labor rich countries receive capital when migrants remit money home. The loss of labor in the old country also increases the wage rate for those who do not emigrate. When workers migrate, their early care and education generally benefit the country where they move to work. And, when they have health problems or retire, their care and retirement pension will typically be paid in the new country.

African nations have invoked this argument with respect to slavery, other colonized peoples have invoked it with respect to the "brain drain" or "human capital flight" which occurs when the most talented individuals (those with the most individual capital) depart for education or opportunity to the colonizing country (historically, Britain and France and the U.S.). Even in Canada and other developed nations, the loss of human capital is considered a problem that can only be offset by further draws on the human capital of poorer nations via immigration. The economic impact of immigration to Canada is generally considered to be positive.

During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, human capital in the United States became considerably more valuable as the need for skilled labor came with newfound technological advancement. The 20th century is often revered as the "human capital century" by scholars such as Claudia Goldin. During this period a new mass movement toward secondary education paved the way for a transition to mass higher education. New techniques and processes required further education than the norm of primary schooling, which thus led to the creation of more formalized schooling across the nation. These advances produced a need for more skilled labor, which caused the wages of occupations that required more education to considerably diverge from the wages of ones that required less. This divergence created incentives for individuals to postpone entering the labor market in order to obtain more education. The “high school movement” had changed the educational system for youth in America. With minor state involvements, the high school movement started at the grass-roots level, particularly the communities with the most homogeneous populations. As a year in high school added more than ten percent to an individual’s income, post-elementary school enrollment and graduation rates increased significantly during the 20th century. The U.S. system of education was characterized for much of the 20th century by publicly funded mass secondary education that was open and forgiving, academic yet practical, secular, gender neutral, and funded by small, fiscally independent districts. This early insight into the need for education allowed for a significant jump in US productivity and economic prosperity, when compared to other world leaders at the time. It is suggested by several economists, that there is a positive correlation between high school enrollment rates and GDP per capita. Less developed countries have not established a set of institutions favoring equality and role of education for the masses and therefore have been incapable of investing in human capital stock necessary for technological growth.

The rights and freedom of individuals to travel and opportunity, despite some historical exceptions such as the Soviet bloc and its "Iron Curtain", seem to consistently transcend the countries in which they are educated. One must also remember that the ability to have mobility with regards to where people want to move and work is a part of their human capital. Being able to move from one area to the next is an ability and a benefit of having human capital. To restrict people from doing so would be to inherently lower their human capital.

This debate resembles, in form, that regarding natural capital.

See also

- Capital (economics)

- capital accumulation

- Capitalize or expense

- Five Capitals

- Human Capital Management

- Human development theory

- Individual capital

- Instructional capital

- Intellectual capital

- Labor power

- Natural capital

- Social capital

- Theodore Schultz

Notes

- ↑ Sullivan, arthur; Steven M. Sheffrin (2003). Economics: Principles in action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. pp. 5. ISBN 0-13-063085-3. http://www.pearsonschool.com/index.cfm?locator=PSZ3R9&PMDbSiteId=2781&PMDbSolutionId=6724&PMDbCategoryId=&PMDbProgramId=12881&level=4.

- ↑ [1] Smith, Adam: An Inquiry into the Nature And Causes of the Wealth of Nations Book 2 - Of the Nature, Accumulation, and Employment of Stock; Published 1776.

- ↑ Pigou, Arthur Cecil A Study in Public Finance, 1928, Macmillan, London, p. 29

- ↑ Hanushek, Eric and Woessmann, Ludwig: The role of cognitive skills in economic development, September 2008, Journal of Economic Literature, 46, pp. 607-668. Rindermann, Heiner: Relevance of education and intelligence at the national level for the economic welfare of people, March 2008, Intelligence, 36, p. 127-142.

- ↑ Marx, Karl. Capital, volume III, ch. 29 pp. 465-6 of the International Publishers edition

- ↑ The Emancipation Question in New-York Daily Tribune, January 17 and 22, 1859

- ↑ http://www.lewrockwell.com/dilorenzo/dilorenzo164.html

- ↑ http://www.lewrockwell.com/block/block112.html

References

- Gary S. Becker (1964, 1993, 3rd ed.). Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-04120-9. (UCP descr)

- Ceridian UK Ltd. (2007) (PDF). Human Capital White Paper. http://www.ceridian.co.uk/hr/downloads/HumanCapitalWhitePaper_2007_01_26.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-27.

- Samuel Bowles & Herbert Gintis (1975). "The Problem with Human Capital Theory--A Marxian Critique," American Economic Review, 65(2), pp. 74–82,

- Sherwin Rosen (1987). "Human capital," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 681–90.

- Seymour W. Itzkoff (2003). Intellectual Capital in Twenty-First-Century Politics. Ashfield, MA: Paideia, ISBN 0-913993-20-4

- Brian Keeley (2007). OECD Insights; Human Capital. ISBN 92-64-02908-7 [2]

- Rossilah Jamil (2004). Human Capital: A Critique. Jurnal Kemanusiaan ISSN 1675-1930.

External links

- New papers and articles on human Capital, a free Newsletter edited by the RePEc academic Project

- Human Capital, Gary Becker The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

- Human Capital Management (HCM) research papers, Softscape Whitepapers.

- OECD Insights: Human Capital - a primer

- Jurnal Kemanusiaan, Bil 04 Dis 2004 (ISSN 1675-1930). Faculty of Management and Human Resource Development